“Prussian field marshals do not mutiny.”

-Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, when asked to join the plot against Hitler.

At the time this was said, this amounted to a lie. The Beer Hall Putsch that Hitler was imprisoned for was, after all, co-led by Field Marshal Ludendorff. Nor was that the first time the officer corps had mutinied; in 1920, officers carried out the Kapp Putsch and the Reichswehr refused to act against them. As Hans von Seekt said, “Reichswehr do not fire on Reichswehr.”

We can therefore consider Manstein less-than-honest when he appealed to the honor and loyalty of the Prussian officer to refuse opposing Hitler. The officer corps offered its fealty (even debasement) to right wing dictators and the coups that swept them to power. Only a few extended true loyalty to the Weimar Republic. Fewer still could muster the courage to oppose Hitler, even when it was clear his policies would lead Germany to ruin.

Claus von Stauffenberg, who placed the bomb that nearly killed Hitler, (made famous by his portrayal by Tom Cruise in the film “Valkyrie”) was motivated not primarily by moral outrage at Nazi policies, but by the belief that the war was lost and a negotiated settlement was Germany’s only hope. There were, of course, many motivated to resist by conscience, but it easy to overstate the humanitarian concerns of the German officer corps. In this way, the July 20th Plot can be used as an alibi for the German officer corps, contributing to the “clean Wehrmacht” myth.

With that background and disclaimer, we may move on to the main purpose of this post: using the plan of Operation Valkyrie to look at the strategic logic behind coups. By using this case and comparing it to the attempt to overturn the US 2020 election, we may identify common threads to coups and more clearly understand the strategic motivations that dictate their component actions.

Anatomy of a Coup

1. Destabilization

“Crown jurist of the Third Reich,” Carl Schmitt, identified the concept of a “state of exception,” similar to a state of emergency. This is a situation in which the sovereign is justified in acting extra-legally because of its urgency. Schmitt identifies the “sovereign” as whatever group of individual acts in the crisis. A crisis of this kind is needed to execute a coup because public opinion is biased towards the status quo. For radical change like a coup to be accepted, the option of preserving the status quo must be removed.

It is in this state of chaos that the coup plotters aim to act, “restoring” order and using the urgency of the crisis to justify abandoning all processes and precedent. In a crisis, after all, there is no time for votes in the legislature, let alone decisions by courts or by election.

The destabilization does not need to be instigated by the coup plotters. Indeed, the coup that brought Hitler to power was prompted by the Reichstag Fire, an incident caused by a Dutch communist. All that is needed is an excuse, which can be manufactured. The Reichstag Fire, after all, was not a true crisis; one man set fire to a government building. Nevertheless, the incident was dramatic enough to provide cover for Hitler to claim that a communist revolt was in progress and convince President Hindenburg to suspend civil liberties.

Some kind of dramatic incident helps the odds of a coup, but the “state of emergency” can be declared on an entirely fabricated basis. Elections are a common target for this approach. Irregularities are rarely obvious and so claims of rigging are difficult to disprove. An election means inherent uncertainty as the locus of legitimate power. Coup plotters may therefore use an election and alleged irregularities as a strong pretext with which to “restore order,” seizing power in the name of democracy. Nascent democracies that fall into dictatorship often go by this route.

This was the method attempted by the Trump campaign in 2020. By broadcasting false accusations of rigging and finding lawyers willing to launch spurious lawsuits, the campaign sought to sow doubt. Likewise, the fake elector scheme was designed not to supplant the legitimate electors, but to make them contested. These elements were coordinated with the aim of creating sufficient uncertainty that a seizure of power by undemocratic means would be accepted as a restoration of order. As we will later discuss, this effort failed.

In the case of the July 20th Plot, the means of destabilization was the assassination of Hitler. The method was a suitcase bomb in a conference room that failed to achieve its intended effects because it was coincidentally moved behind the leg of a table, mostly shielding Hitler from the blast. Decapitating the autocratic regime would have thrown Germany into chaos. The status quo would be irreversibly broken, and while other actors such as the SS would have sought to consolidate power, the vacuum offered the necessary opportunity for the plotters to make a claim to be the legitimate sovereign.

The basic prerequisite of a coup then, is that existing order be disrupted, even if this disruption is manufactured or merely perceived. There must be some kind of crisis that de-legitimizes the old regime and demonstrates that order must be restored. To borrow Schmitt’s terms, there must be a state of exception so that it is—for a moment—unclear who the sovereign is. In this emergency, the plotters aim to step forth and prove their status as sovereign by guaranteeing order. It is this step that will occupy our next section.

2. Seizure

The saying goes that “possession is nine-tenths of the law.” For states, the same holds true. This is to say that by seizing the state apparatus the coup plotters seek to inaugurate themselves as the new status quo and gain at least quasi-legal status. By becoming the status quo, they may avail themselves of the advantages of the bias in that direction. Opposition would have to create a new destabilization in order to perform a counter-coup. For this reason, the opposition will resist the seizure, seeking to prolong the chaos while to organize against the coup. If neither side can swiftly overcome the other and both sides fail to seize the state, the product is civil war.

Returning to Carl Schmitt, his theory is that whichever force steps forth to act in the state of emergency shows itself to be the true sovereign, as it is capable of acting when all the trappings of law are suspended. Few people today would accept this theory. The idea of “popular sovereignty,” that all legitimate power can only come from the consent of the governed, has no real ideological challengers. Yet, Schmitt’s theory provides some practical insight for those of us that do not share his dictatorial sympathies. The proto-liberal theorist, Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), identified the fundamental role of the state as maintaining security and avoiding the anarchic state of nature, which he describes as a war of “all against all.” The state must therefore be a “Leviathan,” a great force able to crush civil conflict, to deter the violence of private individuals. Schmitt’s state of exception is a situation in which it is unclear who controls the Leviathan. There is no power ready to prevent civil war and private violence threatens to become ubiquitous.

Despite widespread belief in the principle of popular sovereignty, it is clear that many people prioritize the establishment of a Leviathan over whether it is done democratically. This preference is understandable, as the alternative is civil war or even a failed state, where things approach the idea of the war of all against all. When staring into that abyss, many people (both members of the public and figures in power), will prefer the devil-you-know and accept whatever sovereign has presented itself. This is, of course, by no means a guarantee of passivity. When facing domination by political enemies, there are many that will prefer a leap in the dark. If a coup is merely in progress or has failed to firmly establish itself, dislodging the plotters may not seem difficult. As such, the immediate aim of the coup plotters is to gain control over the security apparatus so that opposition can be dealt with as criminals rather than on the battlefield.

It is for this reason that coup plotters have the immediate goal of legitimation; they must establish themselves as the continuation of the Leviathan and convince the apparatus of state to follow their directives. A cloak of legality or consensus is valuable. In this stage, support from trusted institutions, elder statesmen are valuable. Likewise, the approval of rump-legislatures is useful, even if they do not have the formal power to do so or if the measure is passed at gunpoint. Plotters may also seek support from the media and encourage their supporters to hold rallies and marches to signal popular consensus.

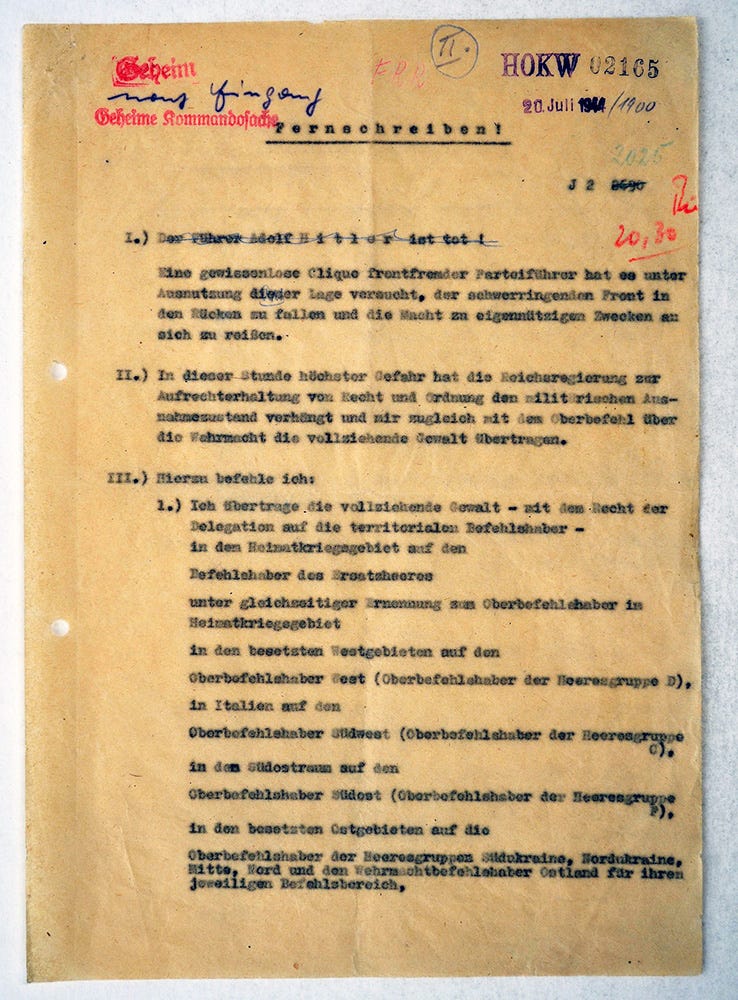

The July 20th plotters intended to use the German reserve army to seize power on the home-front. “Operation Valkyrie,” which the coup attempt is often called, was in fact a pre-existing operation designed for quelling an uprising on the home front. The plotters modified the existing operation to act as a coup. By using an existing plan and issuing orders from legitimate authorities, the coup plotters aimed to avoid the appearance of a coup.

"The Führer Adolf Hitler is dead! A treacherous group of party leaders has attempted to exploit the situation, to betray the hard-struggling front and to seize power for their own selfish purposes.

They intended to blame the assassination on members of the Nazi party and claim that it, along with the SS, was attempting to usurp power. This pretext was necessary to carry along those that were unwilling to commit an act of rebellion. The lie that the other side has attempted a coup is a common device of coup plotters. It allows them to present themselves not as Jacobins destroying the old regime, but as responsible leadership restoring law and order. The July 20th Plot failed before it began because, in failing to kill Hitler, there was no vacuum to fill. Within hours, Hitler was able to issue orders to crush the conspiracy.

The strategy of presenting a coup as a counter-coup was also employed in 2020 in the “fake elector” scheme. As has been extensively shown in documents released as part of the Special Counsel investigation, the conspirators knew they did not have the votes to win the election and that the “alternative” slates of electors they appointed were illegitimate and unconstitutional. As aforementioned, they sought to create a crisis by casting aspersions on the legitimacy of the election, making baseless claims of widespread fraud.

The John Eastman memos lay out the theory: The Vice President (or Senate Pro Tempore Grassley if Pence recused himself), counting the votes as required by the Constitution, would reject the votes from the swing states Trump had lost, citing the competing slates of electors. Trump would then be declared the winner of the election on the basis that he had the most electoral votes of the remaining states. If this failed, the Vice President would refer the matter to the house, where the matter would be voted on by state delegation, of which Republicans controlled a majority.

In one of the most blatant hallmarks of a coup, Eastman insists that the VP must do this without asking permission, in other words, a fait accompli. This was, as explicitly as one can write it, the seizure component. From this, possession of the state would be in the hands of the conspirators. The other side would then have the burden of attempting to overturn the order while the conspirators can declare the matter closed. As the conspirators were currently in government, the seizure phase was very simple. A self-coup requires only acquiescence from the administrative state, whereas an ordinary coup requires the changing of allegiance. As the coup attempt never reached this point, it is unclear how much success it might have had in this regard. The Kapp Putsch succeeded in forcing the government to flee, but ultimately faltered in the face of a general strike and non-compliance from the civil service. One would hope Americans would not allow democracy to be subverted by chicanery, but the alternative would have looked distinctly like a leap into the abyss.

The fake electors plot was unsuccessful primarily because it relied on the support of Vice President Mike Pence, who was ultimately unpersuaded to reject the electoral votes needed or to recuse himself. Long before January 6th, the coup plan was effectively dead in the water. Yet, January 6th offered a chance to revive it. If Pence was unpersuaded by the legal arguments or the allegations that the election was “stolen,” a mob of militia might coerce or convince him. If not, a mob told to “fight” could disrupt certification.

The role of the riot is clear in statements made to Mike Pence. The riot created a disruption which would provide a pretext for denying certification of the electoral votes. The plan to use the fake electors to overturn the election was to be revived from the brink. The legal challenges to the results had gone nowhere. More importantly, Mike Pence was not convinced of its legality (or, less charitably, plausibility). The aims of the rioters were to:

pressure Pence into refusing to certify

delay the proceedings to allow Pence to be pressured

as they said, “hang Mike Pence.”

While there was little practical chance of the third aim, there is a clear logic to the battlecry: if the “meddlesome VP” was gotten rid of, someone more compliant could be appointed. And of course, the threat contributed to the aim of intimidating Pence into compliance—or at least providing him a reason to delay the proceedings more credible than the “kraken” lawsuits. If the certification could not be done safely, that gave a clear pretext to delay it, even if Pence was unconvinced to actively participate in the coup.

This reading of events is further supported by the views of contemporaries. Mike Pence refused to be whisked away by Secret Service agents for fear that he would not be allowed to return to the Capitol if he intended to certify the electoral votes. Even without his agreement, the riot could serve as an excuse to delay certification. The Trump White House could have ordered the secret service to prevent him from returning to the Capitol, ostensibly for his own security.

Then-President Trump also realized the potential of the riot. Mere minutes before the Senate chamber was evacuated he tweeted:

States want to correct their votes, which they now know were based on irregularities and fraud, plus corrupt process never received legislative approval. All Mike Pence has to do is send them back to the States, AND WE WIN. Do it Mike, this is a time for extreme courage!

The connection is clear: Trump hoped the violence of the riot would pressure Pence into going along with the coup.

Further evidence is that after rioters breached the Capitol he tweeted:

The States want to redo their votes. They found out they voted on a FRAUD. Legislatures never approved. Let them do it. BE STRONG!

Congressional leadership also understood the danger. Both Nancy Pelosi and Mitch McConnell moved to quickly reoccupy the building and ensure certification occurred as soon as possible. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Mark Milley, feared the riot would be Trump’s “Reichstag fire.” He, like the other figures mentioned, clearly saw its potential to be used as the destabilization that precedes and justifies a coup.

The aim of the conspirators was to use the chaos of the riot as an excuse to revive and execute the coup as devised by Eastman. The theory relied on Pence refusing certification or recusing so someone could do so in his stead. The insurrection aimed at creating the disruption that the allegations of vote rigging had failed to produce. The hope of the rioters, as established in their prosecutions, was to disrupt the counting of votes in the hope that the outcome could be changed. As demonstrated by the choices and logic of those on scene, there was a serious danger that the conspirators would successfully use the chaos as a pretext for throwing out the votes of the states with slates of fake electors.

The Present, The Future

I wish to make unequivocally clear that describing Jan. 6 as a coup attempt is not mere partisan hyperbole or hysteria. In fact, the coup attempt had begun with the presentation of the Eastman memos to Pence. It had been stillborne because of Pence’s resistance, but the chaos of the riot revived it. There was a new excuse to deny certification and a new chance to further pressure Pence. The riot was not merely a riot, just as the Reichstag fire was not merely a fire, nor was the attempt to kill Hitler merely an assassination attempt. They were each the first “destabilization” phase of a coup attempt. By entering a state of crisis and emergency, the coup plotters seek the Schmittian “state of exception” where they may present themselves as the sovereign.

Hitler succeeded in using the Reichstag Fire as a pretext for abolishing civil rights in Germany because Hindenburg acquiesced. A self-coup often requires little more than compliance from legal or quasi-legal authority. In the state of exception, matters of constitutional interpretation do not have time to be debated.

The sole point that prevented the Jan. 6th coup from proceeding, throwing America into a constitutional crisis at best and civil strife at worst was the refusal of Mike Pence to go along with the plot. While Pence ultimately refused, that outcome was by no means certain. Numerous accounts, including that of former VP Dan Quayle, relate that Pence asked repeatedly whether there was any way he could decline to certify without—in his own mind—violating the constitution. Likewise, on Jan. 6, if Pence had been taken and not permitted to return to the Capitol, there would have been immense pressure on him not to certify. As such, we cannot say how likely the “fake elector” scheme was to succeed. Suffice to say, there are no clear mechanisms for reversing course if Pence had adhered to the strategy Eastman proposed.

As the election nears, therefore, we ought to look carefully for attempts to create the destabilization needed to justify an illegal seizure of power. Alleging fraud can be a means of presenting the conspirators as the guardians of order, rather than a destabilizing force. An election creates inherent uncertainty as to where legitimate authority lies until a winner takes power. In this case, we may take some comfort that the threat is no longer a “self-coup,” and is therefore much more difficult to accomplish. Unfortunately, that is not enough to rest easy. A coup does not need to succeed to cause tremendous damage or to open the floodgates of civil strife. It is for this reason I have chosen to write on the subject, despite this newsletter not being focused on domestic politics. Therefore, let Principiis obsta (“resist beginnings!”) be our guide, and—as with a cancer—let us identify and excise a coup plot early, before a mob nears our Capitol or fake electors are appointed.

Quite excellent. Kudos.

I remember sitting in the Watch Center at the State Department in December 1979 as our embassy in Kabul reported the arrival and initial actions of Soviet invasion forces in Afghanistan. Very early on it was clear by the steps they were taking to control key Afghan institutions that it was in effect a coup d’etat.